My father, part of the Windrush Generation, always said he had a hankering to visit his old haunts back in England before he died. I thought it strange that Vincent Bancroft McFayden continually expressed a longing and nostalgia for his British life because 1947 to 1957 were not the best of times for him or my mother Renie, whom he’d left behind in Kingston.

Not that we talked about it much. It was one of the few sore subjects in my family. Like many immigrant men, my father had taken up with another woman while in England, a fellow Jamaican, and dressmaker, who accompanied him when he secretly returned to the island in 1957. While I wanted to know more about his time in England, I also knew well enough that some things—like that “old business” as both my parents referred to it—were meant to be left alone. So, when I heard about England from my father, it was about his desire for Yorkshire pudding and missing the English climate—“the nicest cool yuh ever feel in yuh life.” Whenever he uttered these sorts of statements, at our dining table on a Sunday afternoon or on a hot July night after long hours out on the road doing the bidding of the Caribbean Construction Company, no one responded. His words simply sat there until they dissipated into the air, just like the smoke trailing from the cigarette between his long dark fingers.

We were to fly over to England in the middle of June. The plan was my mother and I would stay six weeks, while my father would spend only a fortnight, as that was the amount of leave he had from his job at CCC. While in England, we would go between my mother’s brother, Headley, in London, and my father’s brother, Kenneth, in Manchester. Headley had followed my father to England in the aftermath of World War II. That was when the country was looking for workers from their Caribbean colonies to fill the labor void created by the war. As part of the Royal Air Force, Kenneth went to England during wartime. Both my uncles were married to Irish women they’d met in England. The women’s families never spoke to them again since they’d had the audacity to leave whiteness behind and marry “darkies.” Headley and his wife, Kitty, had one daughter, Jane, born six months before me. Kenneth and Lucy had seven children.

I could barely imagine London even though I had constantly looked at pictures of the city in my Encyclopedia Britannica. Besides meeting family, I wanted to look up at Big Ben, walk across London Bridge, see where Anne Boleyn had been kept at the Tower of London, and of course, gaze at the Crown Jewels. My mother meanwhile was nowhere near as enthusiastic. She never commented when my father brought up the weather or the food or the places that he wanted to experience again before he died, from takeaway at local chippy to Speaker’s Corner in Hyde Park. As soon as he was out of our earshot though, she would tell us his longings were those of a man who still didn’t know what was good for him. Nonetheless, Renie McFayden had her own tourist wish list. She wanted us to go see the Changing of the Guard at Buckingham Palace, something I had not earmarked in my encyclopedia. I could not understand her fascination.

Headley met us at Heathrow Airport. My father shook Headley’s hand with his right and slapped his shoulder with his left, saying, “How are you, old chap?” Right after, my mother threw herself into her baby brother’s arms. Headley, six feet, two inches tall, wrapped his arms around her and they stood like that for a good while.

With his curly dark hair, tanned skin, broad shoulders and narrow body, he looked exactly like the pictures he had sent us over the years. There he had been golfing, holding Jane as a baby, dancing with Kitty, taking their Corgie, Whiskey, for a walk. Unlike my older siblings, I had never met him. He’d been gone from Jamaica close to thirty years. I was only twelve. I hung back behind my parents, simply observing how happy all three were, until Headley, one arm still around my mother, pulled me into a bear hug, telling me how glad he was to finally meet me.

“Suzanne,” he asked, “yuh believe yuh reach?

“No,” I answered, and it was true.

I noticed he had a distinct way of speaking. One minute it was full-on countryside Moneague, Jamaica. “Renie, how you do, girl?” The next it was British all the way: “that’s wot I’m talking about, init?”

That was how it was between the three of them the entire ride from the airport to his house, Jamaica and England, back and forth even if Headley’s was the only accent that wove in and out of these two very separate places forever joined by colonialism. Listening to them, I supposed that decades in a foreign country left its mark, even if the years could never erase all that had come before. Headley’s accent rolling back and forth between Moneague and London was outward evidence of this. It made me think of the limited memories my father had shared over time. Life had been tougher than what Jamaicans thought they were leaving behind in favor of England in the 1940s and 1950s. My social studies and history classes that school year had taught me that much. Jamaicans’ services were needed, but they themselves were not wanted. Hearing Headley talk, I began to wonder what else it was my father didn’t talk about, besides the woman he’d shacked up with before returning home, and ultimately reuniting with my mother. What else was in his silence?

Headley drove with my father next to him so my father could have more space for his legs, especially after the long plane ride. My mother and I sat in the back. It was loud in the car as the adults chatted over each other in an effort to catch up among themselves. My parents told Headley about our relatives in Jamaica: my older siblings, Tony, Joan and Bev, had steady jobs; Tony, his wife Marie and their two young sons were doing well; Aunt Lucy (my mother and uncle’s first cousin with whom they had grown up in Moneague) had gotten her Physicians’ Assistant certification; my grandmother Sis was managing okay with her low blood pressure; life was still sleepy in Moneague; political tensions were escalating in Kingston since the shooting of Bob Marley the previous December and since Prime Minister Manley subsequently declared a State of Emergency. Life was getting tougher by the day in terms of less groceries to be found at the supermarket and more and more electricity lock offs (which always seemed to occur the night before I had any big test).

While they chatted, I studied all we went by. I noticed how the gray sky contrasted against the lush greenery that comes from plenty of rainfall as opposed to the dull layer of dust which coated everything in Kingston. How the people on the street were mostly white, something new to me coming from the reverse at home. White or brown, they were all dressed in some sort of coat, some pulling them tighter around themselves against the light wind. Others had scarves wrapped around their necks or caps on their heads. They all walked slightly forward, on the front of their feet, as if continually bracing against a head wind. I noticed too how the trees’ silvery green leaves shivered. That brought me to my own thin pale green polyester pantsuit, the heaviest thing I owned clothing-wise. The insufficient white cotton turtleneck under it, meant to provide extra warmth, was failing miserably. I began to shiver too. England was not contradicting my father on the weather at all except I didn’t find the cool nice. My teeth began chattering right as Headley noticed me from the rearview mirror and said, “Yuh look cold as ice. Let me put the heater on.” Meanwhile, he was not even wearing a sweater. Had my father felt like I did right then when he first arrived in London?

Kitty and Jane met us at their house in Morden—forty-five minutes away from Central London, or London proper as I soon came to think of it. I was disappointed that on the ride we had not seen a single one of the landmarks I’d so eagerly envisioned. We’d gone along the motorway from Heathrow to a neighborhood of streets, all identical to me even as Headley, as if on remote, turned corner after corner to get to the house. Each street had the same two-story, gingerbread-looking white trim, red brick row houses with small lawn or pavement out front and hanging flowerpots abloom by the front door. All was quiet, and I realized most of the neighborhood were likely at work and school given that it was Thursday mid-morning. I suddenly felt very far away from the noise, unending sunlight, and the Jordan almond-pastel blues, greens and pinks of the starter houses in Duhaney Park where I lived in Jamaica.

Kitty greeted us at the front door. “Come in, come in, Vin and Renie. Jane, come down, Suzanne’s here.”

Before she finished talking, she’d turned away. We followed her down a very short hallway to a dining room on the right. She’d set out tea and sandwiches of crustless white bread with ham and butter. As she chattered on, my parents and I hungrily tucked into the food before us, the long flight and jet lag speedily overtaking our excitement at being there. After eating, she and Headley led my parents to the extra bedroom behind the dining room and kitchen. She told Jane to take me up the stairs which were right off the front door. At the top we turned right, passed Headley and Kitty’s room and headed to Jane’s room next door to her parents. I lay down for a minute, but promptly fell asleep, still dressed in my travel clothes.

The six of us next met up for dinner. I was still visibly chilly, enough that Aunt Kitty had Jane run upstairs to get me a few of her sweaters to use during my visit. I immediately put one on and noticed that my mom and I had both buttoned our sweaters all the way up, that we simultaneously said yes when Kitty asked if we wanted her to turn the heat on. My father, however, was in his element, smiling, talkative and dressed only in his typical workday pants and shirt, his sleeves rolled up. He was no longer the tired man I knew from Kingston, the one who left home with me shortly after sunrise on school days, and who usually returned past sunset. His forehead seemed smoothed of its usual thin horizontal lines and the furrows between his brows had relaxed. He looked a decade or more younger than his fifty-five years. It was as if his regular life of work, paying bills, and buying food had fallen off him. The man before me looked and spoke like my father, but he was a carefree version of the man I thought I knew. I smiled happily thinking that on this trip I’d get to know this man I’d never met before.

My mother was different too. Instead of the usual welcoming smile in her blue eyes, she seemed to have added—not discarded—layers, a deep knit taking set between her eyebrows. She seemed skittish, constantly clutched her sweater to her neck and asked my father in a thin, unsure, high voice, “Vincent, yuh sure yuh doan need a sweater? Mind you catch cold, yuh know!”

To which he replied, smiling as he said it, “Relax yourself, Renie, just relax, man.”

After we ate our roast beef, potatoes and peas, the reminiscing began in earnest. Tongues loosened from the rum and coke the adults were sipping. As with all visits we made, even in Jamaica, we’d brought our hosts gifts. This time it was duty-free cigarettes and Appleton Reserve rum. Headley decided to open it in celebration of being with his only sibling again. Halfway through that first drink, when the rum fully hit, Headley showed his hand. When he’d arrived in London, he’d expected my father to meet him at a pre-appointed place and time.

“Vincent, mi wait and wait fi yuh to meet me at Piccadilly Circus and all now mi would still be waiting if it wasn’t fi anodda Jamaican woman who see mi a wait, tek plenty pity pon me and give mi a place fi stay fi two week until mi could find a job.”

“How many times mi have to tell you, Headley, say mi nevah did get di telegram wid yuh arrival time fi know when yuh was coming,” my father said. “By di time I get it, di date done come and gone.”

Headley kissed his teeth. “Nah sah, I tink is busy yud did busy wid odder tings.” He’d lowered his tone as he said this and glanced at my mother who was next to him at the dining table.

“Not dat at all, at all,” my father said in an equally quiet tone, but with no look towards my mother.

After a brief void no one seemed to know how to fill, my father asked Headley if he’d heard from Hammerhead. “Why was he called Hammerhead then?” Kitty asked. Both men laughed and took turns describing how Hammerhead was a short, black, bull-thick Jamaican country man, who’d gotten his name because his eyes were very wide set. As our laughter joined theirs, they got to talking about the light skinned, bamboo reed-thin Johnny (as opposed to the other Johnny who was stout) who couldn’t hold his liquor, and the troubles they’d to get him home after he even so much as sniffed white rum.

My mother though neither laughed nor spoke. She didn’t even move like she would have at home when Kitty, a short, bottle blonde woman with a strong Irish accent, busied herself clearing the table, cleaning the kitchen and getting ready for the next morning. Nor did she turn her head to watch Jane show me her collection of The Rolling Stones albums by the stereo in the living room. It was a group I knew was famous, especially the lead singer with his big lips, but whose music meant as little to me as Bob Marley did to Jane. My mother stayed at the dining table, but was clearly not a part of any unit, not the records, nor the cleaning up, and definitely not the conversation between the men.

When she held her head back and swallowed the rest of her drink Headley asked, “Yuh want another one, Renie?”

“No thank you,” she answered curtly. “I’m going to bed.”

By morning everybody seemed back to normal. Headley, who ran his own carpentry and handyman business left early, but popped in and out from jobs a few times that day to check on us. Jane continued on with her last weeks of school. Kitty went to work at her office job. I began my days of marveling at things like fish and chips from the local pub wrapped in Daily Mirror newspaper and drizzled with malt vinegar, plus teatime with scones, jam, clotted cream, strawberries and Twinnings tea with milk. My father watched my delight and grinned ear to ear. Sunday over dinner I came to realize I did not like the bland, doughy taste of Yorkshire pudding in England any better than when my father made it back home in Kingston. When my father said he was happy to have a break from driving for CCC and just rest his back in bed, my mother and I took walks about the neighborhood.

Headley took us to a flea market on our first Saturday. He thought we would find it interesting because we didn’t have them in Jamaica. I was entranced that the Jamaican women wore their headwraps just as they did back home. I also noticed West African women in long loose robes and open-backed slippers. And bindi-wearing Indian women. All three groups wore sweaters on top of their clothes, tropical butterflies with their wings encased in warm layers. I listened to my countrymen hawking Jamaican black castor oil—good for growing hair and cleaning out the stomach. I noticed thick heavy linty sweaters hung on racks at the back of their stalls. I wondered if they warded off more than just the weather, much the same way the castor oil had multiple uses.

That afternoon, I asked my father when he thought we might go into London proper. I asked him about it while my mother was finishing up in the bathroom off the kitchen. I’d discovered that toilet was very loud when it flushed so I asked right as she pulled the handle down because I didn’t want to arouse any anguish in her. My hope was he and I could go with both our consciences clear. I said it would be a treat for us to give my mother a break, let her be the one to rest one day. You could show me Piccadilly Circus, I said, and the streets you used to use. He took a sip of his tea while I rushed on, saying, I want to see where you lived. I imagined he would also show me where he ate and laughed, that I would see the man I’d recently been introduced to, the man who existed before I’d been a twinkle in his eye. It felt both traitorous to, and protective of my mother, but I figured we were already so close I had nothing to lose by asking.

“Time will come,” is all he said, and kept on sipping.

Friday, the week after we’d arrived, my Uncle Kenneth rang the doorbell. He’d driven down from Manchester to pick us up and take us back with him to meet his side of the family.

Headley answered the door. Standing in the small foyer the two men engaged in the usual chit chat, a “How’ve you been lad”, from Kenneth, a “good good” response from Headly and a “no complaints” from both on how each other’s family was doing. After my dad hugged Kenneth long and hard, we all moved into the dining room to eat the cheese and tomato sandwiches and hot tea Kitty had left out for us.

Between bites, Kenneth said it was “damn good” to see everybody again and asked, “What’s it been now?”

“Must be close to fifteen years, init?” Headley replied.

“I reckon it has,” Kenneth said, and everyone nodded in agreement on the figure. I tried to think what it must be like to go ten years in the case of my parents, fifteen years for my uncles and my father, without seeing someone who once was as known to you as breathing.

At home in Kingston, in the older photo albums, there were many pictures, black and white and hand-colored too, that my parents had sent to each other. They were signed, “To my darling Vincent,” or “To Renie, from your loving husband.” There were sepia-toned ones of each of them too, plus Tony on a rocking horse, Joan smiling shyly, and Bev beneath a cherry tree, my mother’s faded handwriting on the backs telling the children’s ages, 8, 5, and 2 years old. Since they’d both written the dates on the pictures they’d sent each other, I could see they had stopped arriving with the same urgency and frequency as they had at the start. I wondered if there’d been a gradual drifting, longer and longer pauses without communication, as minutes turned into months turned into years? Or, had it been acceptance of what was, of a separation they had decided on for the fiscal good of the family?

While I was thinking about my parents and their pictures, Kenneth said, “We’d best be getting on the road, folks. Got quite the ride ahead of us.”

“That’s for sure,” Headley agreed and my uncles loaded our suitcases into Kenneth’s car for the four-hour drive north.

“See you soon,” we said to Headley as we folded into Kenneth’s car. I wondered what my parents had said to each other when they parted. There was no point asking because I’d get the usual answer from both of them, the “who can remember now from all those years ago?”, even though I couldn’t see how one forgot something like that.

Uncle Kenneth was a shorter, slenderer version of my father, the same dark hair and chocolate skin and elegant limbs, but he spoke with a Northern English accent. At the rest stop we used to break the trip, I knew he was speaking English when he asked me if I was hungry, but he went so fast it took me a lot of “Sorry?” or “Can you say that again, please?” to give him any reply. So, he simply placed what he thought I would like on my cafeteria tray, a sandwich, chips and a drink. But that day and over the next week I began to understand that a mashed peas “butty” was a sandwich with mashed peas in the center, any “butty” in fact was a sandwich, that a “cuppa” was hot tea. Unlike Headley whom I mostly understood, my Uncle Kenneth’s and his family’s accents were as thick and sludgy as Jamaican cocoa tea. But it didn’t bother me at all that I didn’t understand a single word.

It was already 7 pm when we arrived at Kenneth’s house. Its interior was similar to Headley’s. But while Headley’s was semi-detached with a garage, and they had a small plot of roses out back that my aunt Kitty tended along with her front door flower boxes, Kenneth’s front door simply opened onto the street. Inside, it was narrower than Headley’s too, damper, the stairs steeper and everything more worn. It had the dilapidated air of a well-used and well-loved club, especially when all Kenneth’s family fully assembled that night to meet us. Keith, Kenny, David and Carol still lived at home. But the older children, Tony, JoAnn, and Annemarie, their spouses and children, also came over. Just remembering everyone’s name was a feat. By the time they all left, it was close to midnight, and everyone was on a high from meeting each other. I fell into bed as heavily as I had the day I arrived at Headley’s. All that newness was as exhausting as it was exciting.

When I woke the following morning, I realized I liked the feeling of a world that was at once familiar and strange. I could see myself in the faces of my cousins, mash-ups like me race-wise. And I’d heard my father talk about England. But meeting my British family and being in England was completely new and different. It was as if my world had been turned on its head. I could never have imagined this reality based on pictures I’d seen or what my father had shared. Neither he nor my encyclopedia, for example, had described what it might feel like to be a brown person in a white person world, what I could only think of as candied fruit peel scattered across a vanilla cake. This was true on just about all the streets we walked or drove along. My father had also never described what it felt like to be a hot-weather person in a cold climate. Maybe he’d set it aside. Maybe he’d disremembered once he returned to Jamaica and was truly warm again whether inside or outside. In my uncles’ lives on the other hand, we were always trying to get inside, to keep the damp and cold out, but we were never truly successful. There was never any sustained respite. And it seemed to me that there never would be any equal distribution of anything either: not of warmth, of color or of accents, no parity in anything I’d experienced so far.

It was odd that the things I’d taken for granted before, assumed existed most places, did not. Like sunny days. At home, cloudy days were rare. I took it as a personal affront when one arrived. Just as it was an excitement when a temporary cold front, meaning temperatures less than seventy degrees, blew across Jamaica. It was hard to understand that the reverse was the reality in England: cloudy and cool with a chance of drizzle ninety percent of the summer time I was there. I greeted Jamaican heat by staying indoors and got annoyed when it was too hot to be outside in the middle of the day. But any time it was sunny and warm those six weeks in England, the British celebrated the way Jamaicans would have welcomed the second coming of Jesus: with a curry goat feed to which all were invited. That is what it felt like to me anyway, the four or five rare days when that sunny and warm combination occurred. People spilled out of buildings and onto sidewalks everywhere. They milled around their local pubs, evening into night if it happened during the week, afternoon into night if it was on a weekend, pints in hand, one topic of conversation only: the weather and how much they were enjoying it.

“Great day eh bloke?” one would say.

“Right luvly, mate,” another would answer, and they’d all raise their pints. “Cheers mate! To the weather.”

Some, clearly unused to weather I still found quite cool, were flushed to the extent that I finally understood why the few white people I regularly saw back home—my geography teacher, Mr. Harris; the drama teacher, Mrs. Gooden; my father’s boss, Bloomfield, and the door-to-door male Mormon missionaries—were always red-faced from the heat. Most of the people I saw saying they were enjoying the day looked flushed too. If 70-ish degrees did this to them, it was no wonder the constant 80s and up back home took such a toll on the pale-skinned foreigners I knew.

For the first time, I completely understood celebrating every glorious day of sunshine. I celebrated myself, by unbuttoning my sweater. Still, if this was summer, what sort of fortitude must my father and uncles have had to withstand year after year of what I could only imagine winter would feel like. Even my father, who insisted he loved and had missed the cool had, after two days, added in the sweater my mother began suggesting the minute we set foot in Heathrow airport.

In Manchester, my mother was a lot more like the person I knew in Jamaica. She was lively again, even if she still clutched her sweater round about her, holding it extra tight at the neck. Her voice was no longer thin as it had been in London, and her shoulders had dropped down from her ears. I supposed that was because my father had never lived in Manchester, that she thought there were no ghosts hiding round corners, waiting to jump out and remind her of her ten-year purgatory. There should have been nothing to call up being a single mother of three waiting for her husband to either send for her and their children or to come back home himself. Nothing to make her wonder if the other woman was the reason why the pictures he’d sent had stopped coming as frequently as time passed. Nothing to make her wonder why when he came back he hadn’t told her, hadn’t rushed right round to their house, taken her in his arms, swore to her and their children he’d never leave again.

My uncle’s family was rambunctious from first light out until velvet again covered over the day. Their noise filled my head completely, reminding me of home and the noise of my own brothers and sisters. There was nothing tourist-wise I wanted to see in Manchester, but my cousins were far more interesting anyway. We shared blood, yet they were so different from me with their mostly sandy blond hair, their very pale skin, their Beatles-looking bell bottom pants and fitted striped knit shirts with white collars, their rounded vowels and hard consonants. Kenneth, unlike Headley, had not been so diligent in sending pictures and the only one I had seen was of him and my father wearing felt hats and wool overcoats, walking down a London street, each holding one hand of JoAnn who was a toddler in the photo, with my Aunt Lucy, Kenneth’s wife, to his left. I had never seen the rest of the people now calling me “cuzzin” and whose faces resembled mine mostly in the pointy chin my father and Kenneth shared. To some degree it was like watching myself and my siblings in a fun house mirror.

In London, my mother had often remarked her amazement that daylight went on pretty long on European nights versus Jamaica, where somewhere around 7 pm night fell as quickly as the clothes I dashed to the floor on my way to bed each night after I finished studying. Like her, I found the long evenings incredible. So, I sat in wonder on the sidewalk, not far from her and my dad on our first Saturday night in Manchester. I watched my cousins, sometimes Keith and Annemarie alone, sometimes Kenny and JoAnn making it a foursome, play badminton. They’d strung up a net between two lamp posts on the shady, tree-lined cul-de-sac where Annemarie lived. Close by were her husband, Phil, ruddy faced from his homemade lager and the warm evening. He was chatting with my dad, who was now yet another iteration—“Vinny ”—to everyone except my mother and me. Phil and Annemarie’s two young blonde-haired sons chased each other and their first cousins from JoAnn’s and Tony’s marriages. My Uncle Kenneth, Aunt Lucy and their other children were there too, folded into lawn chairs strewn across Annemarie’s front yard. “Bloody hell”-this, “bloody murder”-that and “utter rubbish” lobbed between chairs like the shuttlecock across the net. I could see all clearly, see who said what, as if it were 5 pm back in Kingston, the sky just a bit duskier. I stole a look at my black-strapped Timex wristwatch, saw it was well after 9.

The same ritual from London had occurred in Manchester too the night before. My parents handed over duty-free cigarettes and Appleton Reserve rum, but more of both than at Headley’s as Kenneth had more people demanding a share. Like Headley, Kenneth had opened a bottle of rum the first night. It finished quickly so he’d brought an unopened one to Annemarie’s and made drinks for the adults. Some of them were double fisting it, Phil’s lager in one hand, a rum and coke in the other. But the drinks soon emptied.

Kenneth got up. “Alright,” he said, “I’m heading inside. Who wants a top up?”

“That’s right, old man,” one of my older male cousins said. “Get back inside and fetch our drinks. You’re embarrassing us with that skin color of yours. You’re lucky we let you sit out here with us, you know. People might think we’re related or sumthin’.”

All his family laughed, heartily, in the way of a joke that’s well worn, not new or shocking or thought about in any way beyond its familiarity and retelling. Much the same way, I thought, that his family probably no longer noticed the dampness or the steep stairs or the comfortable yet worn edges I’d spotted right away entering my uncle’s house the night before. I had never noticed my dad’s skin before either, that it was so much darker than mine. And yet in that moment, I saw Vinny and Ken completely differently, the only two dark-skinned people between all of us.

It made me remember the day I forgot my lunch at home and my father brought it to me at Alpha. He’d come up to the classroom and I’d raised my hand and asked Mr. Harris, my geography teacher, if I could step outside to get something from my dad.

“Where is he?” Mr. Harris asked.

“Right there,” I said, pointing at my father who was beckoning at me with hand to hurry up because he had to get back to work.

“Are you sure that’s your father?” Mr. Harris said.

And the entire class burst out laughing because everyone at school knew him and thought Mr. Harris must be going blind. It had not occurred to me until that Manchester evening that it was the difference in our skin color that had brought about Mr. Harris’ question. My father hadn’t heard Mr. Harris, so we’d never discussed it.

That same night in Manchester I realized that must be why my grandmother Sis also sometimes grumbled that my mother could have done better than my father. Until right then my dad had always been just my dad. All that was good on him was good for me too. Now I wondered what would happen next since no one seemed to be paying any particular attention to what had been said.

“Cheeky bastards, right lot of you,” Kenneth retorted, “taking the mickey out of a poor old man. Oughta be ashamed of yourselves, right Vinny? If they only knew the half of it, the half of what you and me lived through!”

“Aye sah,” my father said, “dese young people have no idea how it was for us, yuh know? Memba what it was like to even try and find a place to live when I first come over?”

“I do,” Kenneth said.

“A sign in the window saying room for rent and then the minute the door open and they see your face, they either tell you they don’t rent to people like ‘you,’ or the more decent ones would say the room jus’ gone before you come. Like the whole of we was idiot and couldn’t see what dem was doing. And when we did manage to find a place, is a whole heap of we crowd up like sardines! But it was that or nothing. When we leave Jamaica, nobody thinking anything was going be like that.”

I breathed as quietly as I could, willing the men to continue.

“You tell them, Vinny,” Uncle Kenneth said, his voice thick with both emotion and rum. “We all thought getting here was going to be like shooting fish in a barrel, didn’t we? Serve the Motherland as rightful citizens and all that, and we would make some good money too. I was lucky I was in the RAF. But the rest of you trying to find jobs, well that was downright painful, wasn’t it? Even getting the worse ones, sweeping up somewhere, building stuff, emptying bedpans at the hospital or working your fingers to the bone in one of their unheated factories or on some bloody awful construction site was hard. But Royal Air Force and all, we come here to help them, didn’t we? But treated worse than dirt, we were, as if the black would somehow rub off and stain them. And yet it was them who invited us here.”

“And the cold,” my father went on, “bwoy, dat was anodda ting altogether. I never know I could cold like that, like the ice was inside my bones, like a hungry dog that not letting go of a piece of meat. Man, I couldn’t get it out of me no matter what I did, even on the days when the hot water at that first house I lived at didn’t run out. Remember that place Ken? The one with the crazy landlady that kept renting out the same room although three or four of us were already packed in there, sleeping in shifts?”

“Yes, and you’d have to tell the poor new fellow what was what.”

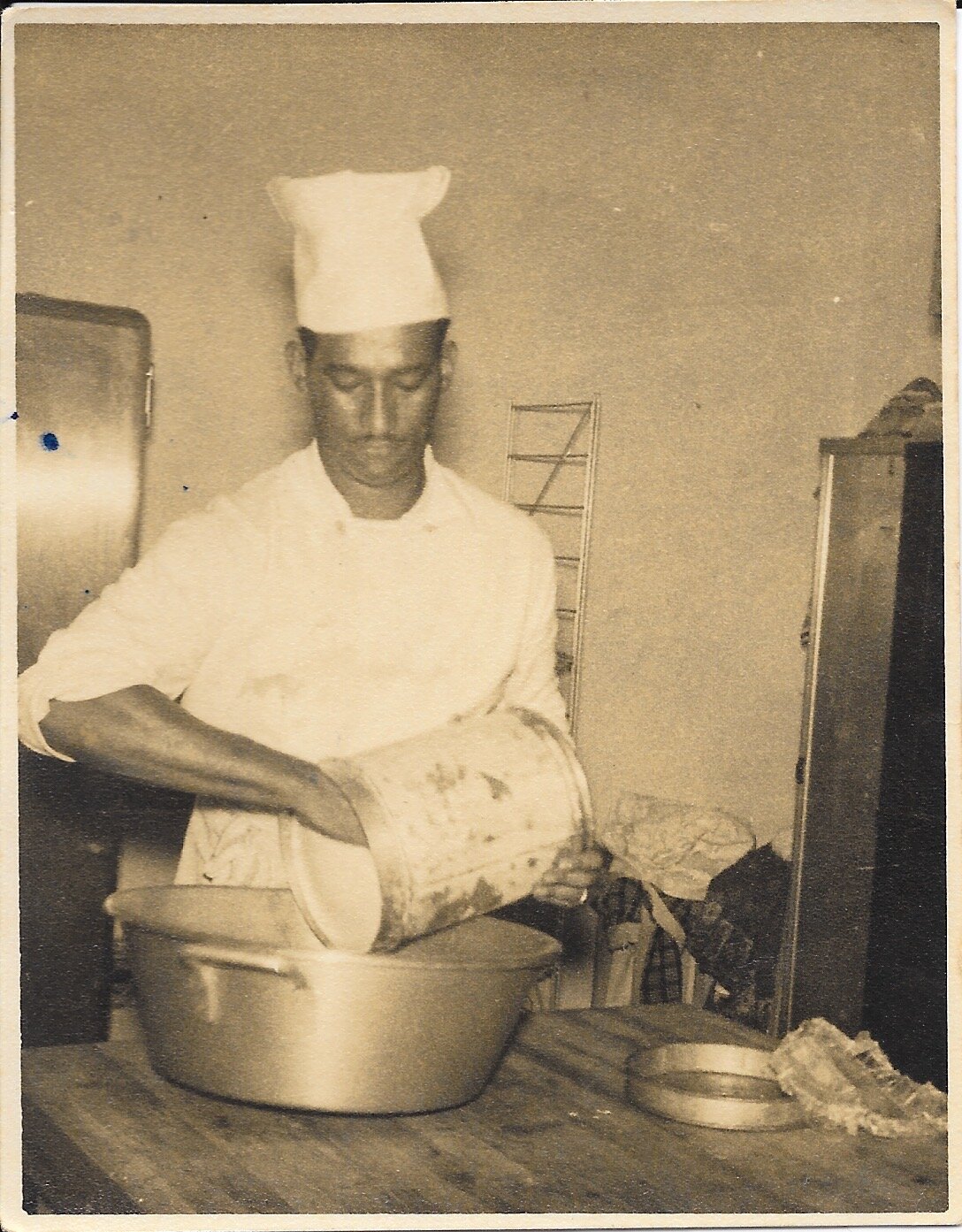

“Usually we’d let him stay the night tho. Because when she got drunk and wanted to come in and ‘fraternize with us’ we’d get her to give the money back and him could start looking again in the morning. I swear I only took that chef course so I could be in a kitchen and near heat on a regular basis.”

Kenneth started laughing. “I was glad to see you get out of that place. I don’t know what was worst, her, the crowding, or the cold. I guess they were about equal in the end, right?”

“Well, lucky for you, Ken, I came along, didn’t I?” my Aunt Lucy said in her Irish brogue, a sly cheekiness to her voice. “None of Vinny’s bad times for you!”

She was quieter than my Aunt Kitty, the same short haircut, but brown instead of blonde, always puffing on her cigarette and pushing her heavy-framed brown glasses up the bridge of her nose. From what I’d seen and heard so far, she wasn’t a woman of many words, but she seemed to have found the right ones for my uncle’s ears.

“Right you did, love,” my uncle said. “You came along, warmed up my cold heart, and other places.” He winked at her. “And which of us didn’t need some warmth in those dark days?”

“I know I did,” she answered.

He held his hand out towards her and said, “come on then, luv. Come give your fellow a hand.”

She took it. He helped her up from the chair and together they went back inside the house to make fresh drinks.

Their words and shared memories had clearly brought them into an intimate moment. For my mother, those same words were a call to ghosts to come out and play. Ghosts she thought lived only in London. After Lucy spoke, my mother became pale and folded in on herself again, arms across her chest, looking like a small bird unexpectedly pushed from one of the trees above us, dazed and trying to get its bearings.

“Is true,” my mother said to only one person in particular, but to no one in general. “We all needed some love in those days.” Her voice was as cold as a day I’d only just experienced for the first time in London: sun lit but without any warmth at all.

I knew my parents’ body language as well as my own. How many times had I used that knowledge to try and get what I wanted, to get one of them to go to bat for me against the other? I had used it when, at eleven years old, I asked my mother specifically after her afternoon nap, from which she always emerged in a good mood, if she would intervene with my father so I could go to a school friend’s party. I knew she would wait until he was finished with dinner that night, was sitting on the verandah, his legs crossed at the ankles and smoking his second cigarette to ask him.

They were right next to each other in Manchester, the arms of their lawn chairs bumping against each other. But I could see as clearly as I could see my watch in the not yet dark night that the ghosts of their ten years on different sides of the Atlantic Ocean and the woman who had kept him warm all those nights my mother hadn’t was pushing them as far apart as England was from Jamaica. I saw it in the way my mother inched her still-seated body slightly away from my father’s, the way he took a sustained puff on his cigarette.

One of my cousins said towards the backs of my aunt and uncle as they moved towards the house to get the drinks, “Ah dad, you got lots of love now, don’t you? Look at all of us! We might take the mickey, but we love you, don’t we lads and lasses?”

And all their adult children gave a resounding, “Aye, aye!” which made the little ones run around screaming and mimicking their elders.

The “aye ayes” lingering on the air, I found myself wondering what my mother had done for her own comfort all those years she was waiting for my father.

It wasn’t my cousins’ hands Kenneth had taken in his. It wasn’t her children’s waists Lucy put her arm around to walk into the house. I knew my siblings and I loved our mom by the way we were always looking for how to please her: doing well in school, helping clean up after meals without her asking us, seeking her advice first on our problems or on our scrapes and bruises. But at twelve and starting to think about boys, hearing girls at Alpha talk with a certain catch in their voice about the boy they had their eyes on at St. George’s, our brother school, I already understood there was a difference between the fiercest love from your child and one from your sweetheart.

My father didn’t say anything to my mother while they sat there, and she didn’t say anything to him either. I easily knew that when they went to bed, they wouldn’t talk, that his silence would be a decree for the rest of their night. I also knew that to the untrained eye, to my cousins, maybe even to my uncle and aunt, everything seemed as it always was, my parents Vincent and Renie, Renie and Vincent McFayden, Mr. and Mrs. Mac, one unit. And yet for the first time, as the light finally left that evening around 10:30 pm, I saw that each of them was a complete whole unto themselves, each maybe thinking that some questions were better left unasked, some answers better left unsaid, some things best left ignored completely.

Getting ready for bed, I thought about my mother going around our house when she and my father had a disagreement she couldn’t quite let go of, but which he’d already made the final decision on. Talking to herself, she voiced her problems, questioned his failure to see things her way until she usually ended by saying, “I only hold my tongue to keep the peace, yuh know.” I started to understand the price of my mother’s silence that night. I saw from her posture earlier that evening how much it must have cost her, the hurt to her pride, to have taken my father back. To have made a family again because of the older children, then added in new ones, including me, without any resentment towards him that I could see. And yet, being reminded of it all unwittingly from time to time. Maybe that was why I thought I should never ask her about it either.

It was only years later, as a freshman at Cornell University, that I came to understand more about the cost to my father, the crushing sense of loneliness when everything familiar has been stripped away and warmth arrives only in bursts: like the capfuls of Overproof Appleton white rum I swallowed on the most bitter nights before climbing between my own cold, damp sheets. The capfuls warm only briefly though and the temptation to take any warmth you can get, even at the risk of hurting others left back home, begin to seem like the only road and one that’s maybe not so bad. Before that time at Cornell, I’d imagined, maybe even the same way my mother imagined, that life simply had to be easier in every way off the island. Why else why would anyone leave in the first place? Or stay away as long as my father had?

The rest of our time in Manchester was uneventful outside of me continuing to say sorry to things I didn’t understand and asking for them to be repeated. Plus a day trip to the beach in Wales where the wind whipped through my clothes, the waves roiled and I saw for the first time that a beach could be cold and made up of pebbles, not the fine white sand I was used to in Negril or out at Hellshire beach. The time also passed quickly with more family get togethers, more fish and chips, and more long summer nights playing badminton.

Uncle Kenneth drove us back to London with a couple days to spare before my father returned to Kingston. After our time in Manchester, I realized my father wouldn’t be taking me to see any of his old spots before he left. There was too much pain all around for that to happen. He loved my mother and she would not ever get over the fact that it was my sister Bev, eleven years old and walking home from school who’d spotted him. She recognized him from the picture my mother kept on a mantle in their house and ran home to tell my disbelieving mother. I knew my father must have resented that he hurt her, both with the woman he’d taken up with and because he often hadn’t been able to send money home to her after paying rent and feeding himself. I imagined it must have been difficult to come back round to the house, hat and heart in hand before my mother and siblings. I briefly thought about asking Headley to take me around London, but I could see he, and Kenneth too, had come far from their early lives and didn’t want to revisit their hard times either.

While my mother made tea, I went into the back bedroom at Headley’s house and watched my father fold his clothes and get his suitcase ready to go back to Kingston. I lay across the top of the bed, my back against the pillows my mother had shaken out and straightened that morning when she made their bed. My father clearly hadn’t forgotten what he’d said to me about the two of us going into London proper, that he’d said, “time will come.” He kept his eyes focused down on the task in his hands as he said, “I would take you, yuh know, into town like you ask me, but I don’t know the tube stations well enough anymore.” He seemed to be a man who had realized what was good for him. He also seemed to put himself on again with those words. That is to say, he looked like the father I knew, the man who paid the mortgage and bought our food and showed us love that way. This was the man Headley drove back to the airport.

After he left, Headley and Kitty both took a couple days off work and took me, my mother and Jane into Central London. One of the days was particularly sunny, and warm enough for me to not wear my sweater though my mother still tucked it and hers into her purse, “jus’ in case.” The first day we went sightseeing, my mother said I was a teenager so our little group should first see all the things I most wanted to. I stared up at Big Ben from its shadow and heard it mark the hour. I watched the ravens hop about the grass at The Tower of London. They were big like the John Crow birds back home, though fatter and sturdier and with thick glossy dark feathers on their heads unlike our “peel-head” vultures. I imagined one of the Queen’s tiaras on my head, but in the end, between my parents’ history and the history of the stones, the Crown Jewels in their vitrines looked dipped in an unappealing, bloody light.

On the second day we did what my mother wanted, although I still didn’t understand her fascination with the Changing of the Guard at Buckingham Palace. Except for the bear-skin hats they looked no different marching than the soldiers on parade at Up Park Camp back home. I kept my opinion to myself as I had not seen her that happy and carefree since the trip began. She nodded her head to the band’s music and even did a little jig at one point. She was like a schoolgirl again. I felt embarrassed at first, but then oddly happy seeing the years fall away from her.

We ended the evening walking through a rose garden at Hyde Park because Headley knew his sister loved flowers. Jane and I lagged behind the adults the way adolescent girls do. Every so often, they turned back to look at us, to make sure we weren’t too far behind. Once when they did, Headley said something only for my mother’s ears. Whatever it was, it made her throw back her head and laugh loud and long. A small breeze rippled her light brown hair away from her forehead and pushed the sound of her laughter out towards me. I’d seen another side of my father during this trip to England. Now I had caught sight of my mother. The sun was against me, but I imagined her anew, on Speaker’s Corner in Hyde Park. She was on my father’s arm. They laughed at something a woman speaker said, and pulled closer to each other, close enough for her to whisper in my father’s ear. He turned to her, smiled, nodded his head, and gave her the last word.

Contributor Notes

Born and raised in Kingston, Jamaica, Suzanne McFayden is an author, leading collector of modern and contemporary art and sponsor of national and international humanitarian efforts to feed the hungry. McFayden holds a BA in French Literature from Cornell University and an MFA in Writing from Mills College. In 2009, she was awarded a coveted spot in the Hedgebrook Writer in Residence program, and was invited to return as an alumna in 2020. Her philanthropic investments continue to expand opportunity for women and children around the world, starting with ensuring that families worldwide have the food they need to thrive. McFayden serves on the boards of the Blanton Museum at the University of Texas, Austin and the Studio Museum of Harlem in NYC. As one of few independent female collectors in the art world, McFayden's personal collection is focused on works that reflect who she is: woman, black, mother, immigrant, traveller, survivor, writer, other.