ANGIE CRUZ: Thank you, Laura Pegram, for all your hard work and generosity, and to all the Kweli writers for sharing the stage with us and those here at the New York Times building for donating this beautiful space.

I am honored to introduce the collective that makes up Desveladas. Before I do that I would like to revisit Audre Lourde’s essay “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action.”

Each of us is here now because in one way or another we share a commitment to language, and to the power of language and to the reclaiming of that language which has been made to work against us. In the transformation of silence into language and action, it is vitally necessary to teach by living and speaking those truths which we believe and know beyond understanding.

We can learn to work and speak when we are afraid in the same way we have learned to work and speak when we are tired. For we have been socialized to respect fear more than our needs for language and definition. And while we wait in silence for that final luxury of fearlessness, the weight of that silence will choke us.

The fact that we are here and that I speak not these words, is an attempt to break that silence and bridge some of those differences between us. For it is not difference which immobilizes us, but silence, and there are so many silences to be broken.

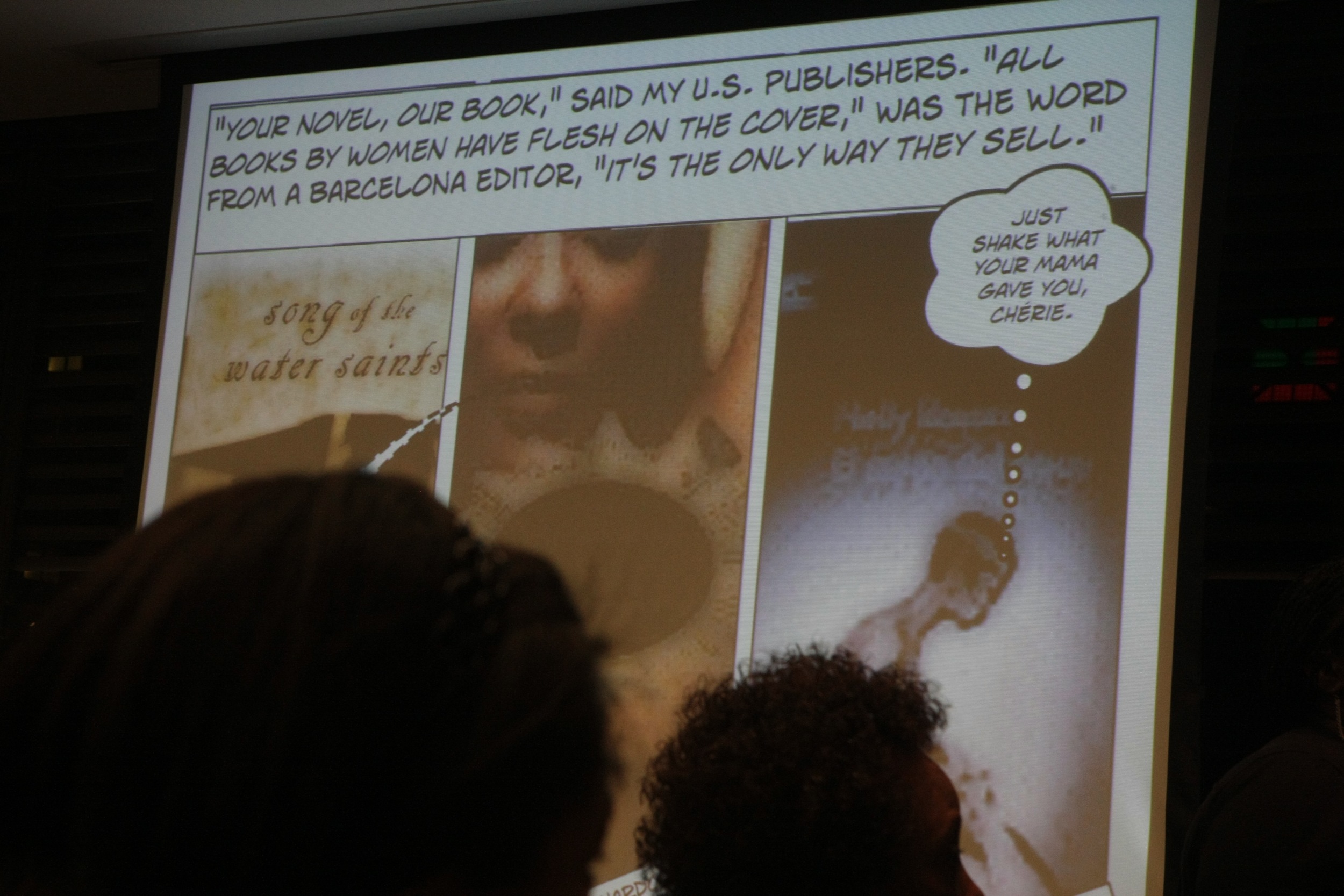

In that spirit, I celebrate these women because their project Desveladas, and the work they do in their lives to break the silences around the border and borders we inhabit, to complicate the narratives we carry and to disrupt our notions of how to talk about it, is not easy. With that said, these panels (slides) that you are looking at are part of the fotonovela in progress and they are raw and still in development. But they are also an invitation to everyone who is here and witnessing them, as they process, to be part of their conversation about the border.

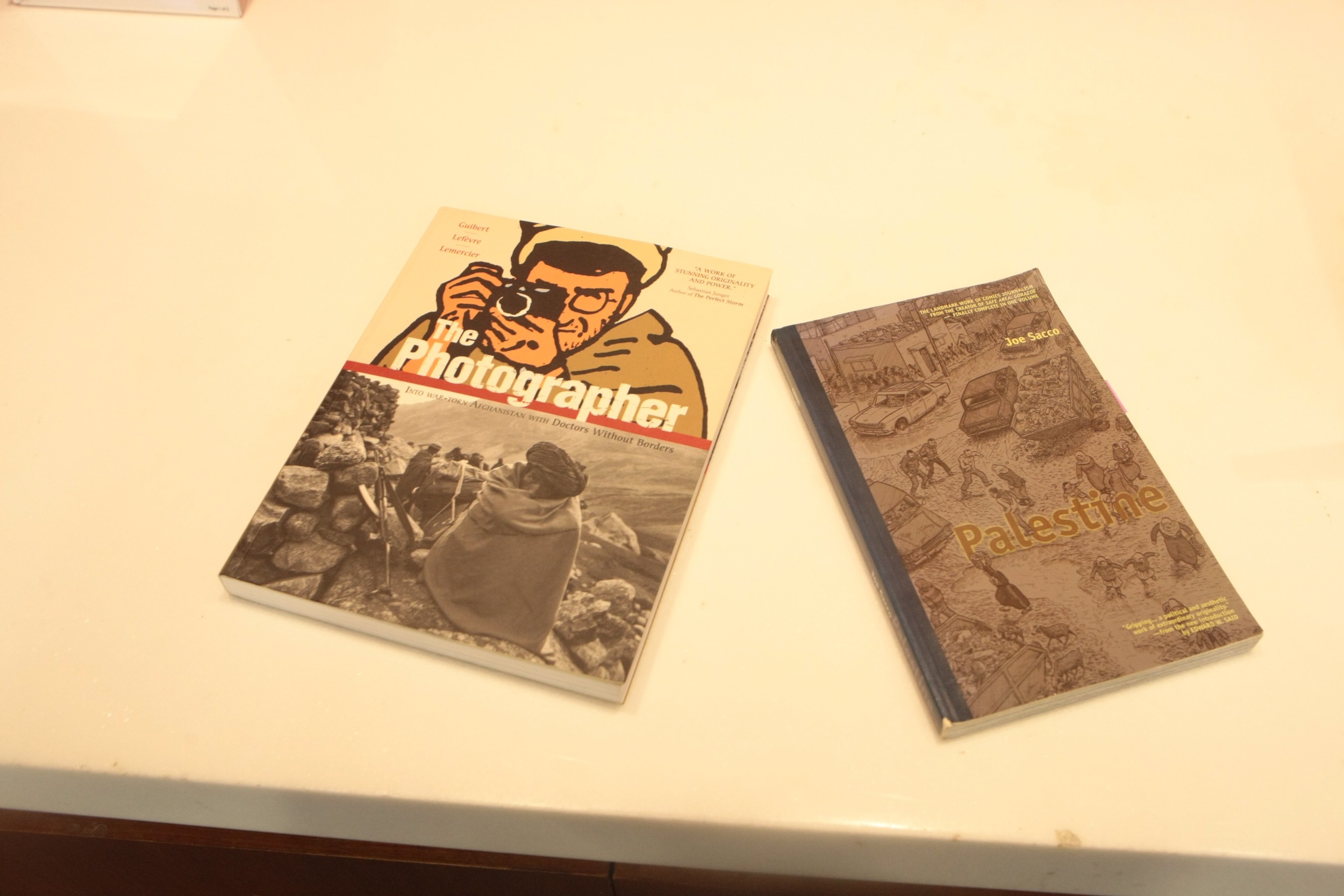

NELLY ROSARIO: We live in an instagram age and we want to find other ways to engage text and the image. Macarena is a journalist, I'm a fiction writer and Sheila is a poet. I think that this sort of intragenre conversation is really important. But there is also the larger conversation, an international conversation, about this whole question of borders. We live in a world that is increasingly violent and sectarian and there are constant divisions. But I feel that it is at that line, at the border, where people are most willing to exchange. It's funny because the line is supposed to define a separation, but at the line is where people are most ambiguous. So that is one of the things we also want to explore in this fotonovela. Tonight I am reading from a novel in progress. What I really want to mediate on is the content of this scene. It is actually inspired by Humpty Dumpty and this slide is from Lewis Carroll's Looking Glass. I really want to think about the edge or the border as a consistent state of being as opposed to it being a sort of marginal state of being. I think we all live on borders, all of us are on borders of something and our job is to make that translation, whatever it is, whether we're on ethnic borders, racial borders, neighborhood borders, artistic borders. We are all bordering on something and I find that really fascinating and I think that this is what Macarena, Sheila and I are always in conversation about. So I want to think about figurative and literal borders. This piece is part of my novel in progress. It's a very dark piece. I'll set it up for you. It's two doctors. They're a couple. They rehab'd a crack house in Brooklyn into a clinic and they're going through a time of crisis. Most of the scene is from the point of view of the wife, and then the second part which, is the last part, is short, is from the point of view of her daughter who eventually becomes a doctor.

Novel excerpt (first part)

So this is your grand rebuttal, I said. To make me a goddamn widow.

My husband was hanging a few feet from the roof ledge and I could only see his fingers. They were clamped around the lip of an ivy planter that ran the length of our roof. Not clamped tight enough though I saw. For sure his feet had to be planted on the protruding bay window of the attic below. For sure. Still the situation was not undangerous. As usual, his infernal silence made my voice rise like a vulture riding thermal winds. Answer me coño, I shouted, and had to lean further over the roof ledge for a better look at this death-do-us-part of our marriage. The planter obscured his face, but beyond the wilted ivys I could see sweat glittering on his bald spot.

Sinvergüenza, I said, counting on my shaky certainty that he had solid footing. In your next life, be more discreet and overdose on castor oil. Just make sure to leave me enough toilet paper on your way out.

Shit. Crisis intervention is not my strength. Neither is forgive forget. We argued last night. Our usual one ways, the nag and the deaf mute. I sent him to hell and promptly took my pillow to the attic. There I could only sleep up to my sixth dream. I was tossing and turning into a seventh when an apocalyptic light in the room woke me. Apocalyptic because the window of the attic faces west. A thump shook the upper quadrant of the bay window, followed by a glimpse of shadow. The world's ending for sure, I thought, if our carrier pigeons are flying into glass too. And then I caught a glimpse of familiar boots, the duck tape ones I told Tomas countless times are unbecoming of a respectable doctor. Of anyone.

Or munch on raw yuca, I was saying presently. Since cyanide is the choice of poets, politicians, revolutionaries.

The magazines too had already given my husband his prescription. One doctor a day tries to kill himself, the suicide rate among males at almost four times the national average. And now a socialist doctor, who writes poetry about the slow genocide of the body politic, aspires to these statistics? The absurdity compañero of a neighborhood waking up to Tomas de Castillo hanging like a white flag from drug den turned clinic. Higher up, braless wife in curlers, house dress, night cream slathered on face, extending broom stick over roof ledge. When the broom stick tip grazed his knuckles, he tucked his long thumbs under his palms.

What is the point? he said finally, but in a voice that might as well have been the croak of a frog hidden in a planter where the ivys had been trampled, some even ripped away.

This Tomas, I said is exactly the point I tried to make last night that your left hand knows everything done by our right. Hadn't you wanted this roof to rival the hanging gardens of Babylon? I said. Hadn't we planted medicinal plants around chimney vents according to his vision? Organized the neighborhood urchins to build a greenhouse from plastic bottles? Convinced friends who worked in the beer distilleries along the east river to haul us rain water barrels for irrigation? Make sure the kitchen scraps were sent up here for composting, fed and treated the destitute, resuscitated this community back to a life that it never had? I put down my double barreled baronet ?? Neither words, nor sticks, nor stones get far with a survivor of family slander in third war prisons. In our thirty years of loving and working, I've come to understand his silences, can even hear when his deaf ear listens and his good ear chooses not to. But there is only so much silence a woman can take before she herself turns to stone.

"Say something carajo, because it is colder than hell's frig on this goddamn tower of Babel. His sun cower behind the racket of a passing truck on the street below. Thank heaven it was Sunday with too many sinners on this block to wake up for the early service at the corner church. And thank heaven the building across the street was under construction that the ghosts there weren't too nosy. There was still time to save face saving this life, so I quieted the raw in my throat that would surely finish ghashing my other half to the pavement. I recalibrated my vocal chords and swallowed my years of swallowing. I forced myself to imagine us, chatty at the kitchen table downstairs instead, separated only by two months of our homegrown honey sweetened coffee. By the way, wasn't it strange, our western sunrise this morning? I said and already could hear his good ear softening. "Did our bedroom get the trick of light too?" His thumb slowly peeked out of his right palm. "Just like you, mi amor, I woke up in that attic thinking that the world was ending." An index finger stirred. "And then I looked out the window and diablo, it turns out the newly installed panes on that window right there, right behind you across the street, were simply reflecting the sunrise." I leaned over in time to see the bald spot catch a glimpse of that same light as his head turned. And there I was, la pendeja, scared stupid by a moment's reflection. What I'm telling you, Tomas, is to look on the bright side. From now on our house will have two sunrises, one in the east and another in the west.

He was sobbing, or pigeons were cooing in a voice that took it's time to uncoil in my ears. "But then we only have one sunrise. Don't you see? I'm a failure in this country."

I covered my ears. It was the first time I heard my husband refer to him in the singular. By now my teeth were chattering. Ah, Tomas, I said. You're a failure because you believe you're a failure because you failed to see that you're not a failure. You who say that I speak in Fibonacci Sequences, you are on a algorithmic spiral downward. That's what I meant last night, but you chose to hear me with your bad ear.

Pointless. Pointless, he said.

Carajo, look around you. Look around us. I open my arms wide to indicate the surrounding garden, forgetting for a moment the difference in our line of vision. It then took an incredible line of empathy on my part to put myself in his duct tape boots and see from the point of view of this suddenly myopic man. Only with my eyes closed was I able to draw out for him what was already in his sights. On our stoop four stories down, right below the circle of yellow chrysanthemums. West directly across the street, the apartment building we put pressure on the city to rebuild. Parked at the corner, southwest, the ambulatory van gifted to our clinic by an anonymous donor. On the wall of an empty corner locked to the south, the mural of a black pieya by the graffiti artist whose asthma we treated in exchange at no cost. From that same corner, the volunteer walking due north to our clinic for his Sunday morning shift.

I opened my eyes. "Four right angle, Tomas. Your so-called failures form a perfect square and we are done with this sob story," was my glossy finish.

Then I heard a sound behind me. The door to the roof opening. Down below, his fingers were now feeling around the planter for a stronger hold. Afraid of losing progress, I did not dare turn around but I shooed away with one hand whoever was approaching.

"Diana, there you are."

It was Tomas' voice, but from behind. And then a breeze smelling of coffee and toothpaste and then my very lucid husband standing calmly beside me. And not below me and me screaming and screaming like one gone irreparably mad and blind and my very lucid husband behind me following my shattered gaze down on to the other fingers that had burrowed themselves deep into the soil of the planter and my screams. And now a train derailed after so many years of stops like clock work, busy medical stations and "I think I can" and next stops and "All aboards" and doors opening and closing and tickets please and green to red lights and then right before a blackout in the tunnel and the screeching brakes and the warm hands of my real husband gripping my shoulders from behind to keep me from flying off the cliff to which our marriage had brought me as I leaned half my body over the ledge of the roof to meet the crossed eyes of the complete stranger who was hanging on for dear life.

* * *

Doctors. We spend a good part of our practice trying to deafen stories. Doctor Mother taught me what the story of the suicidal man has taught her. That if we don't listen patiently, the story of the patient becomes everyone's story. Suicide man, also known as el huevon, he never jumped. But he never got off our roof either. He hangs there to this day, alive though, not undead. That's why we call him el huevon for being too cowardly to choose. When strangers walk through our neighborhood, they stop to look up at the living gargoyle in our building. We feed him. We clothe him in bad weather. The clinic staff even built a tarp shelter for him. Our pigeons are his friends. He's known to tell incredible stories about his thousand lives. "He seems to understand his function in a community with too many good reasons for jumping," says Doctor Father, "that el huevon's presence is a reminder to us of the tenuous, but resilient nature of life." My parents sometimes allow him visits from people convinced they can talk him into coming down from his perch. No one succeeded. The fun is in trying. I have. Many times. But I really want el huevon to stay at the edge forever. Upon that roof, says Doctor Mother, after the scare of her life, the border between to be or not to be is its own sublime existence.